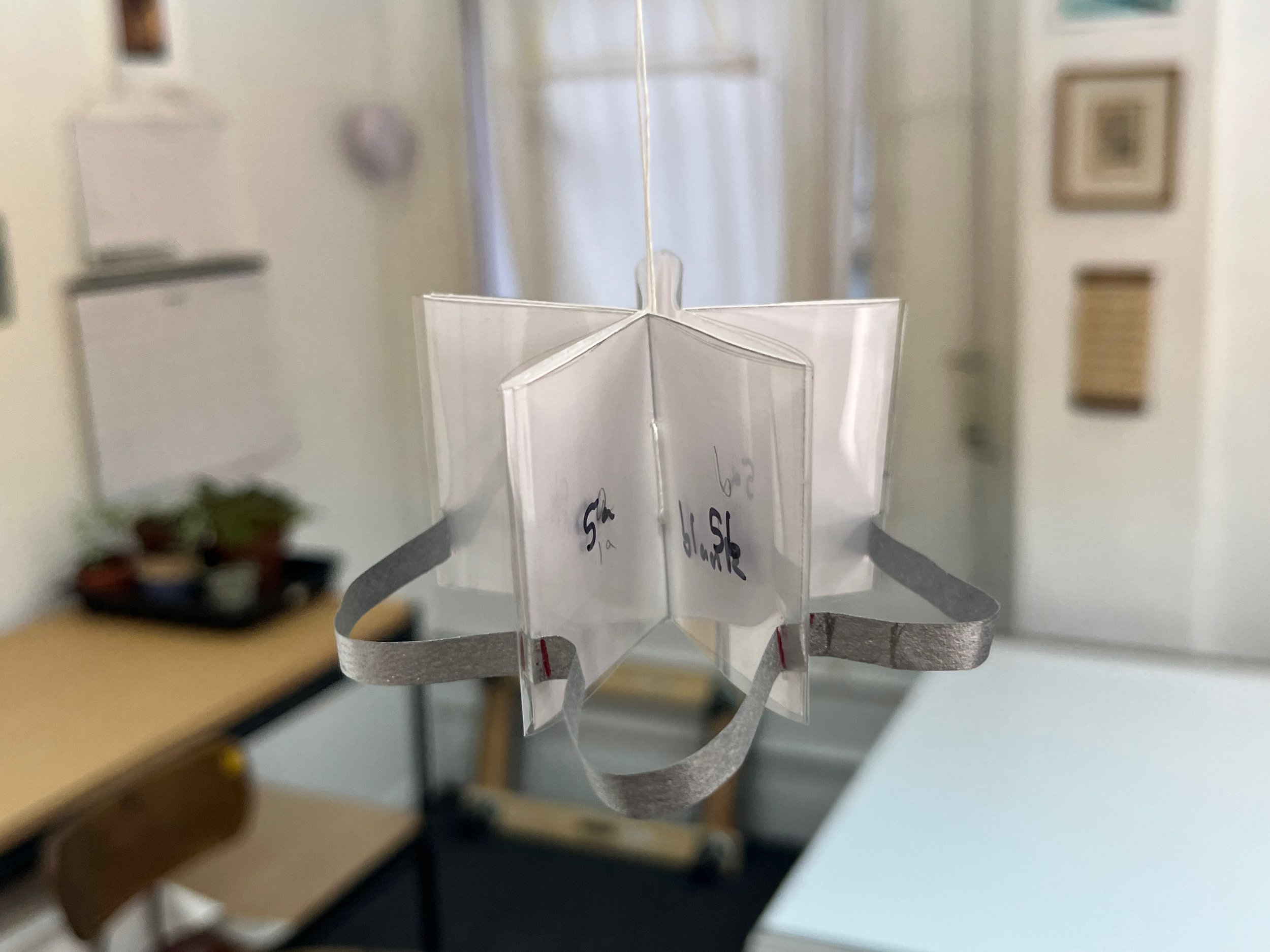

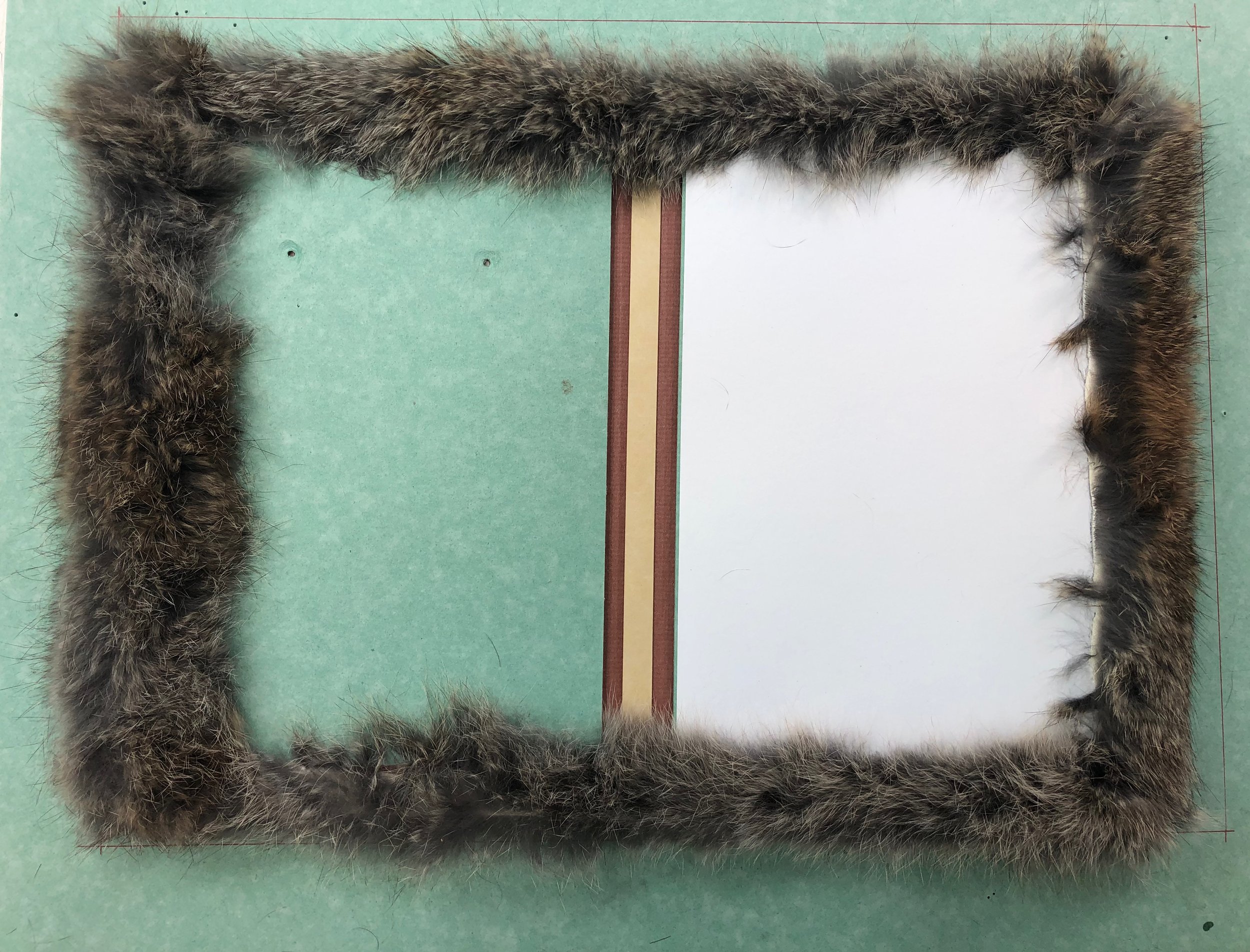

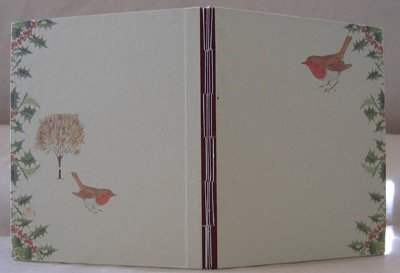

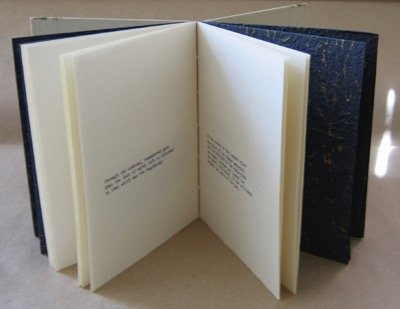

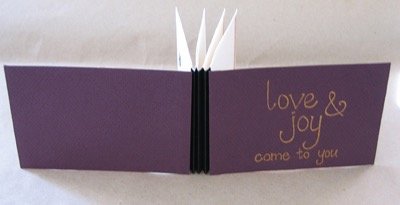

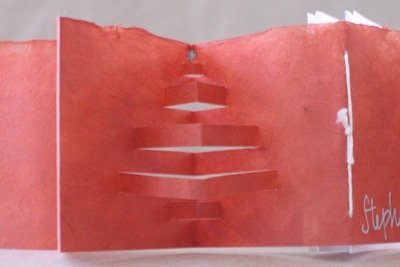

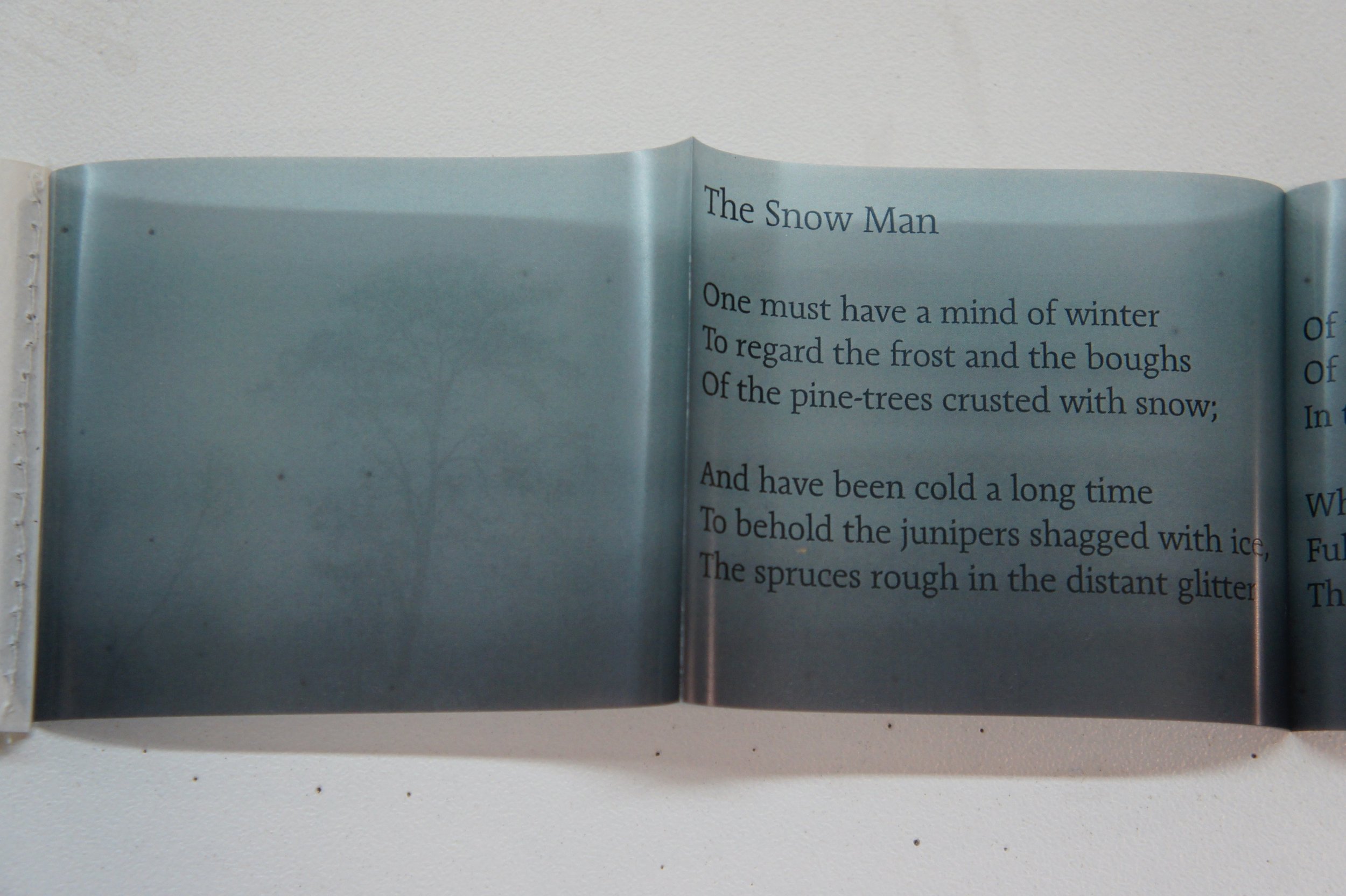

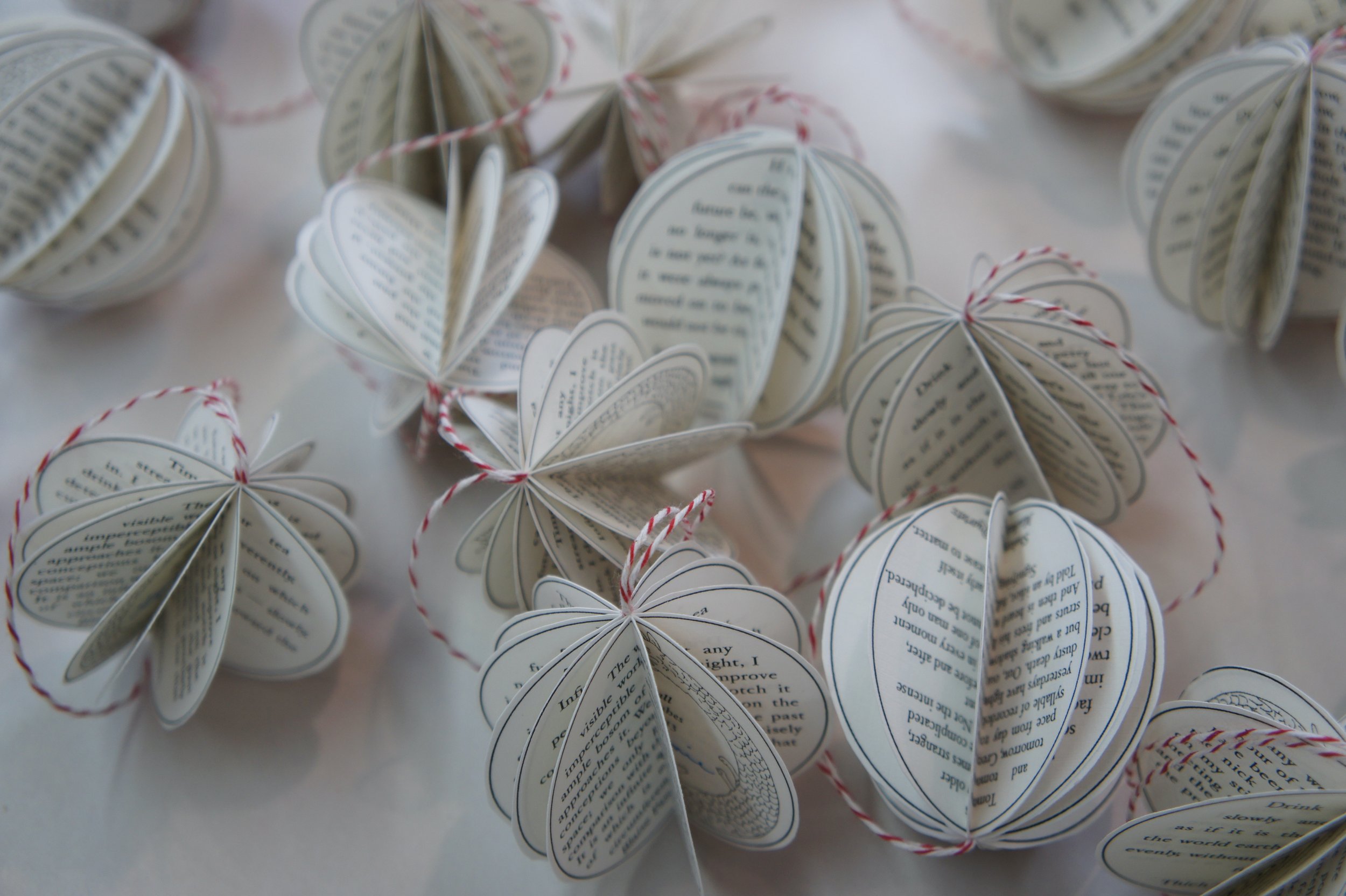

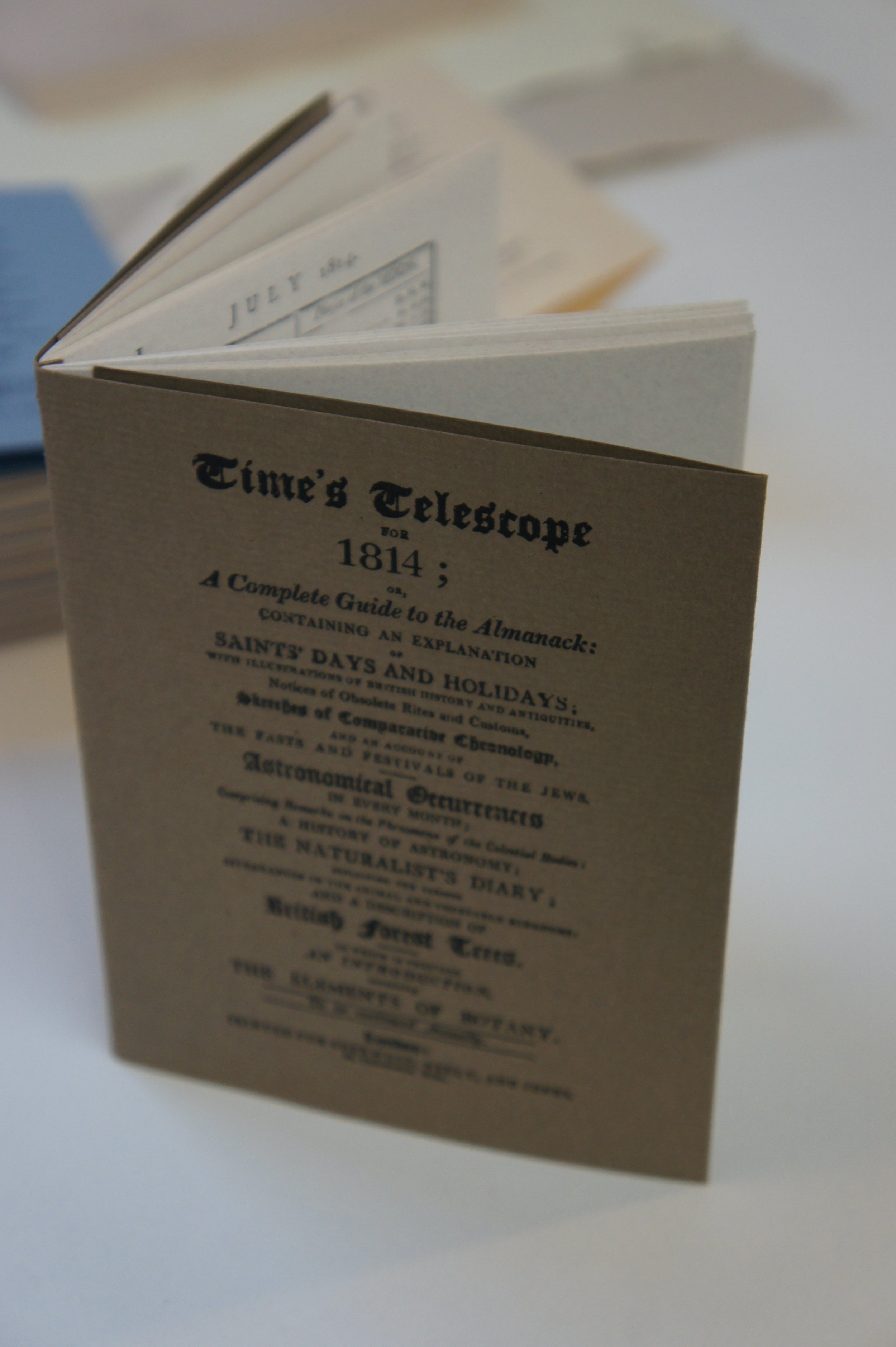

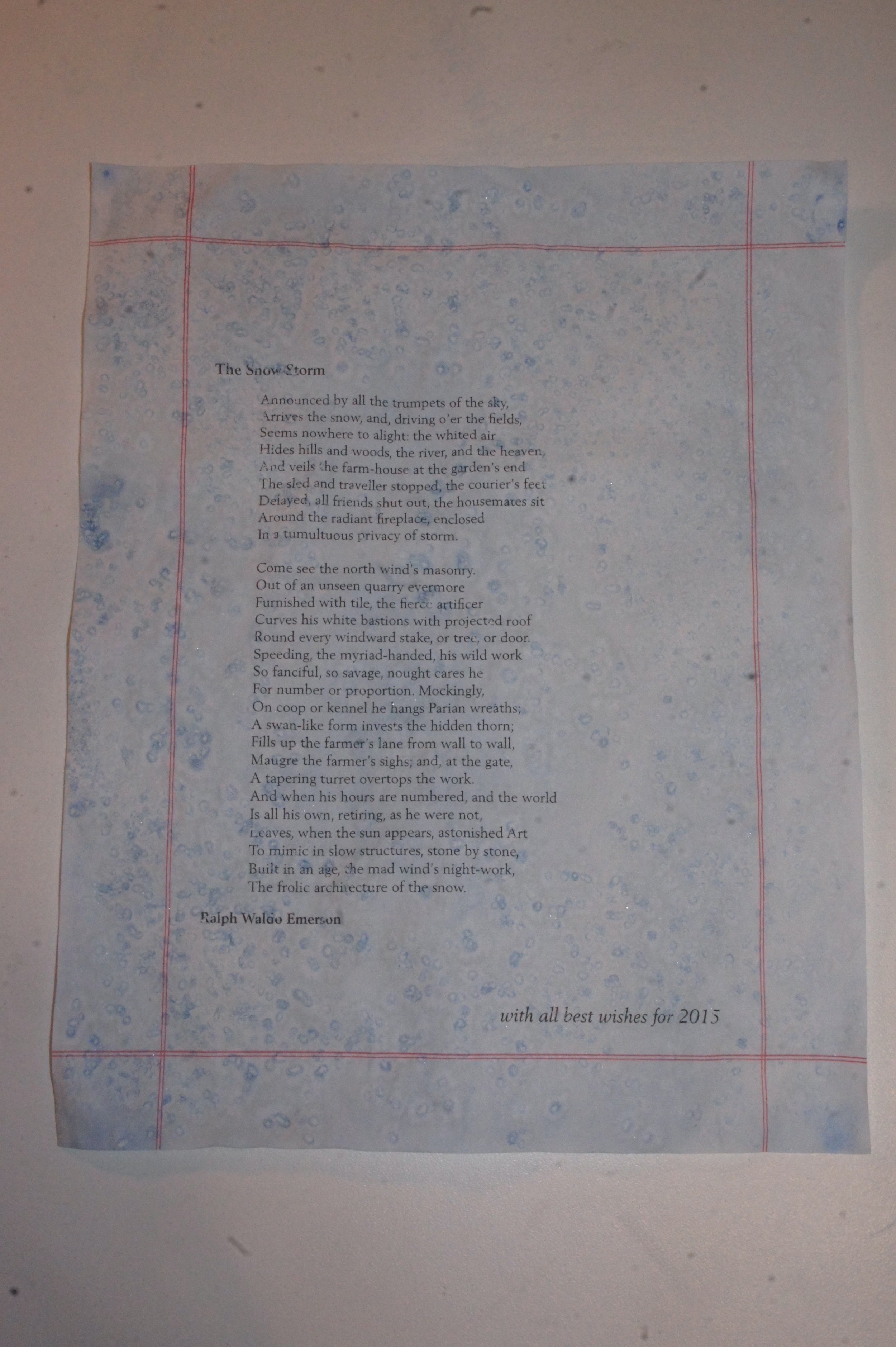

a score of seasons

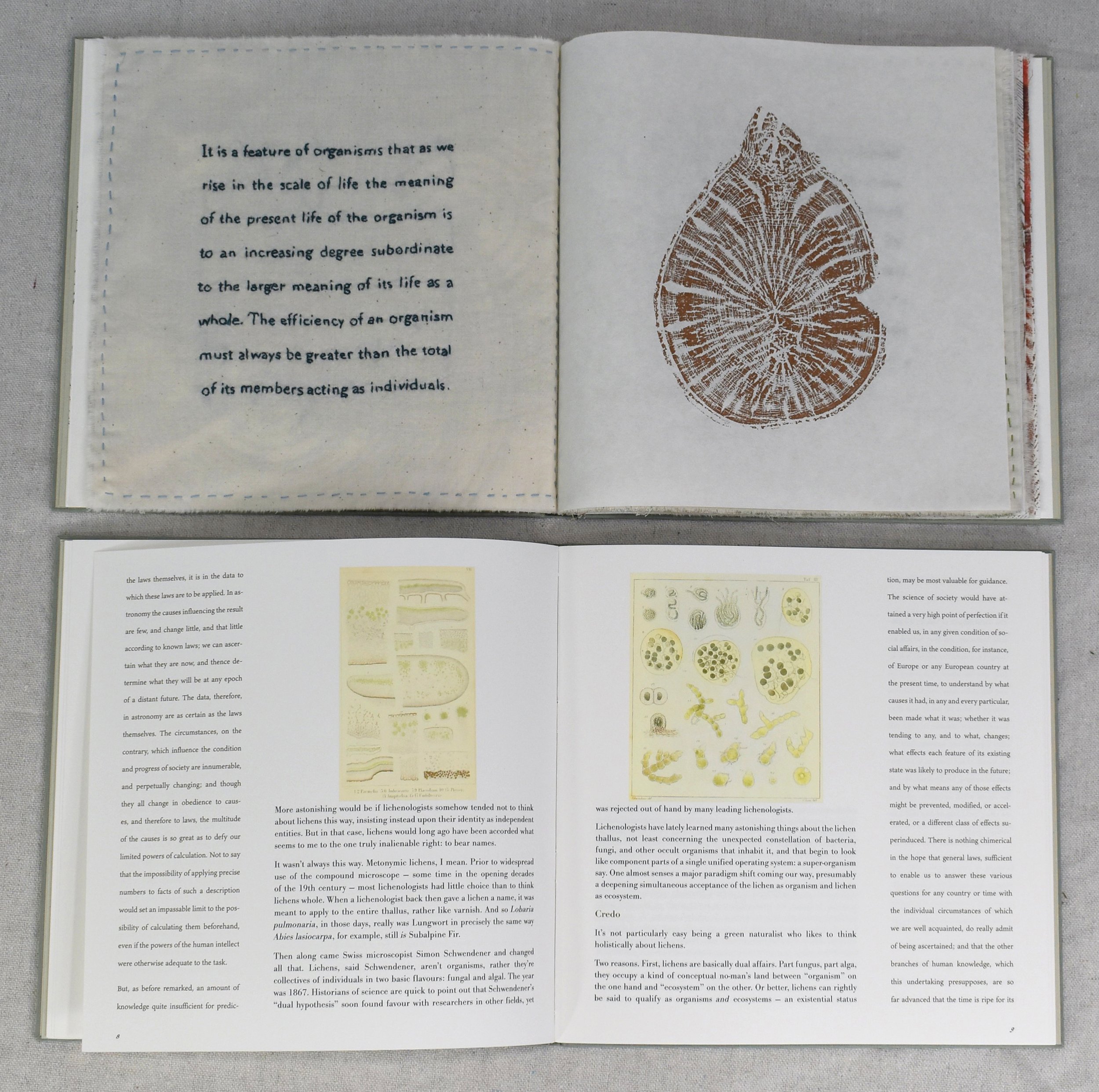

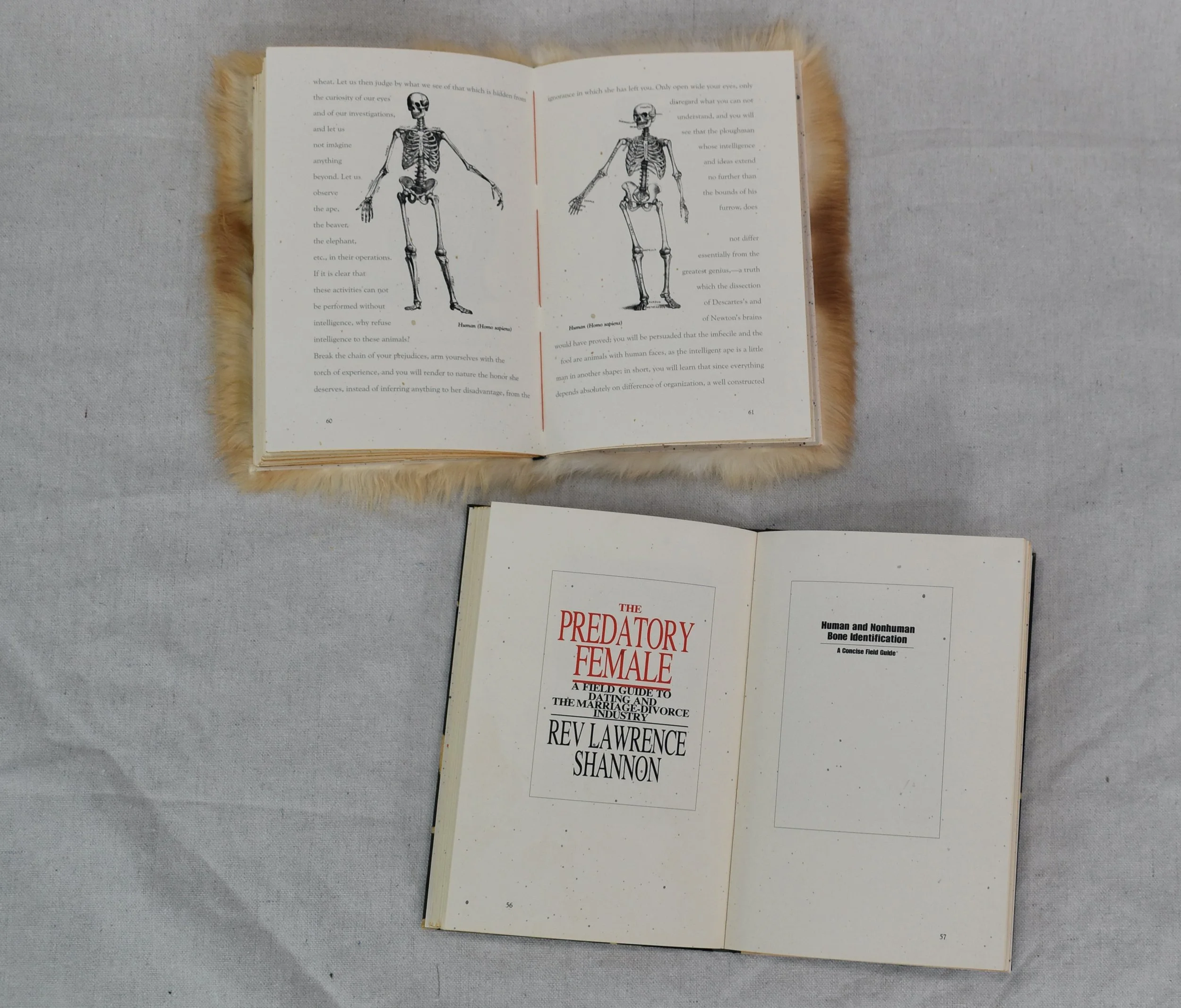

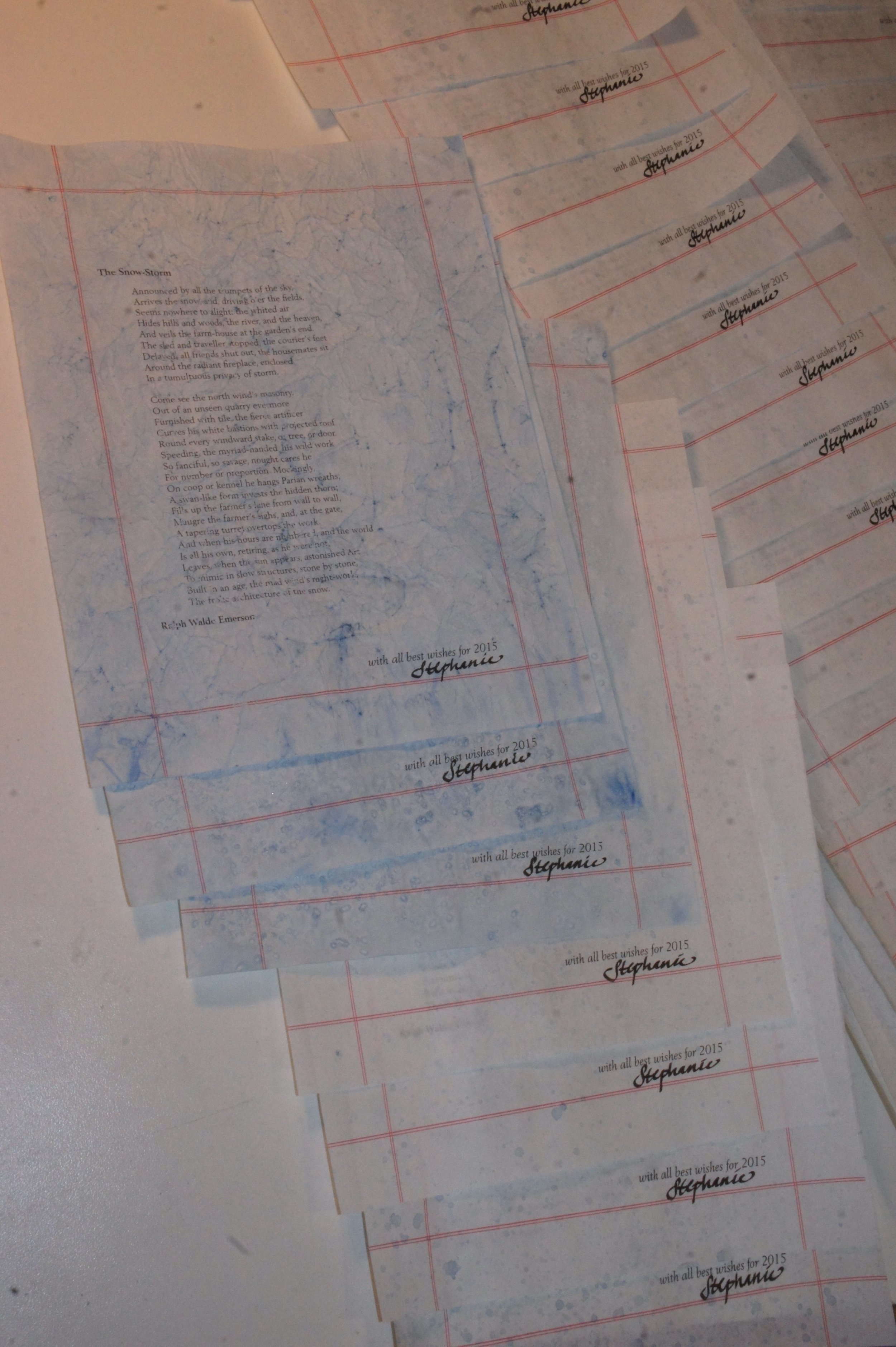

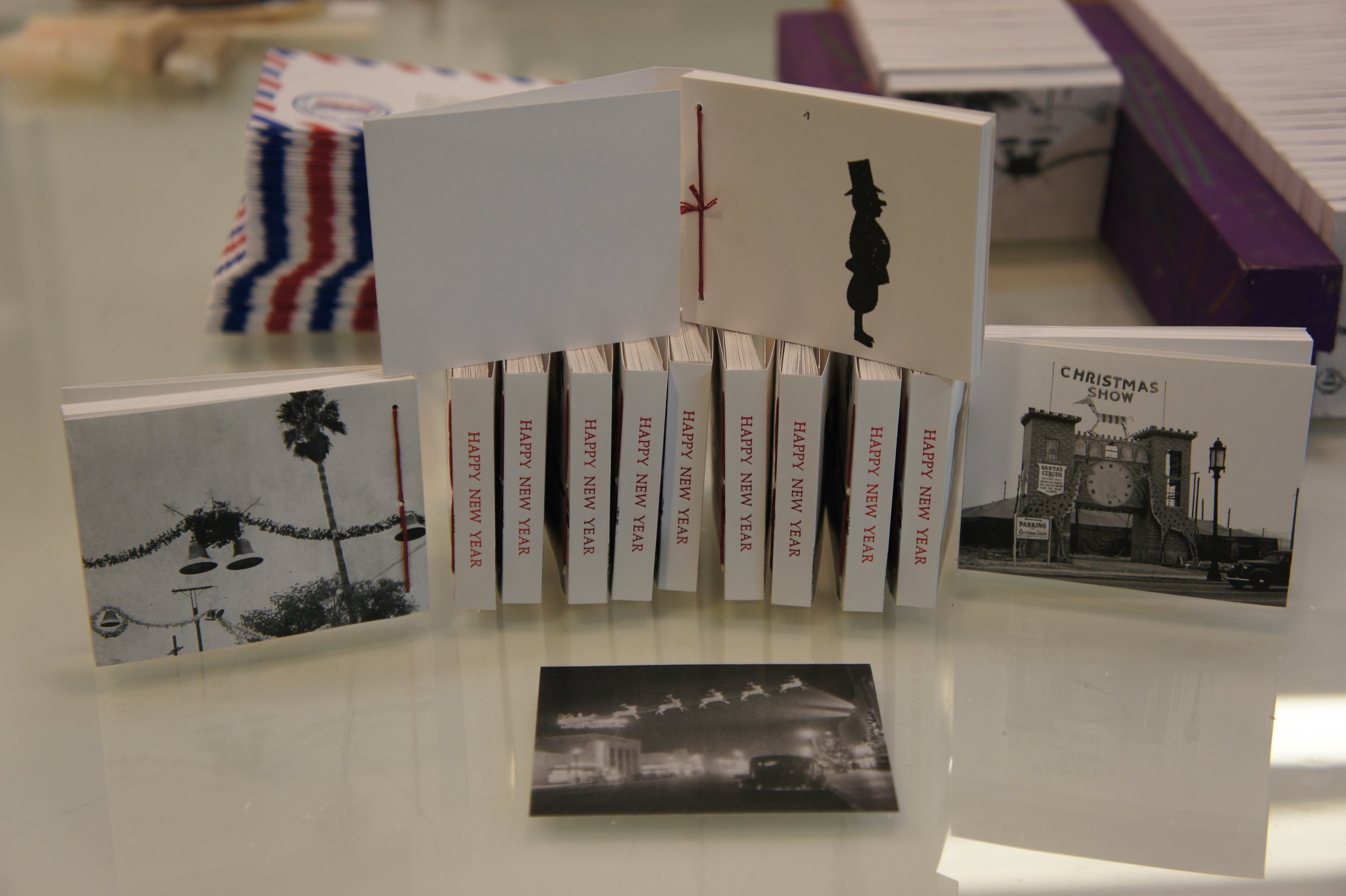

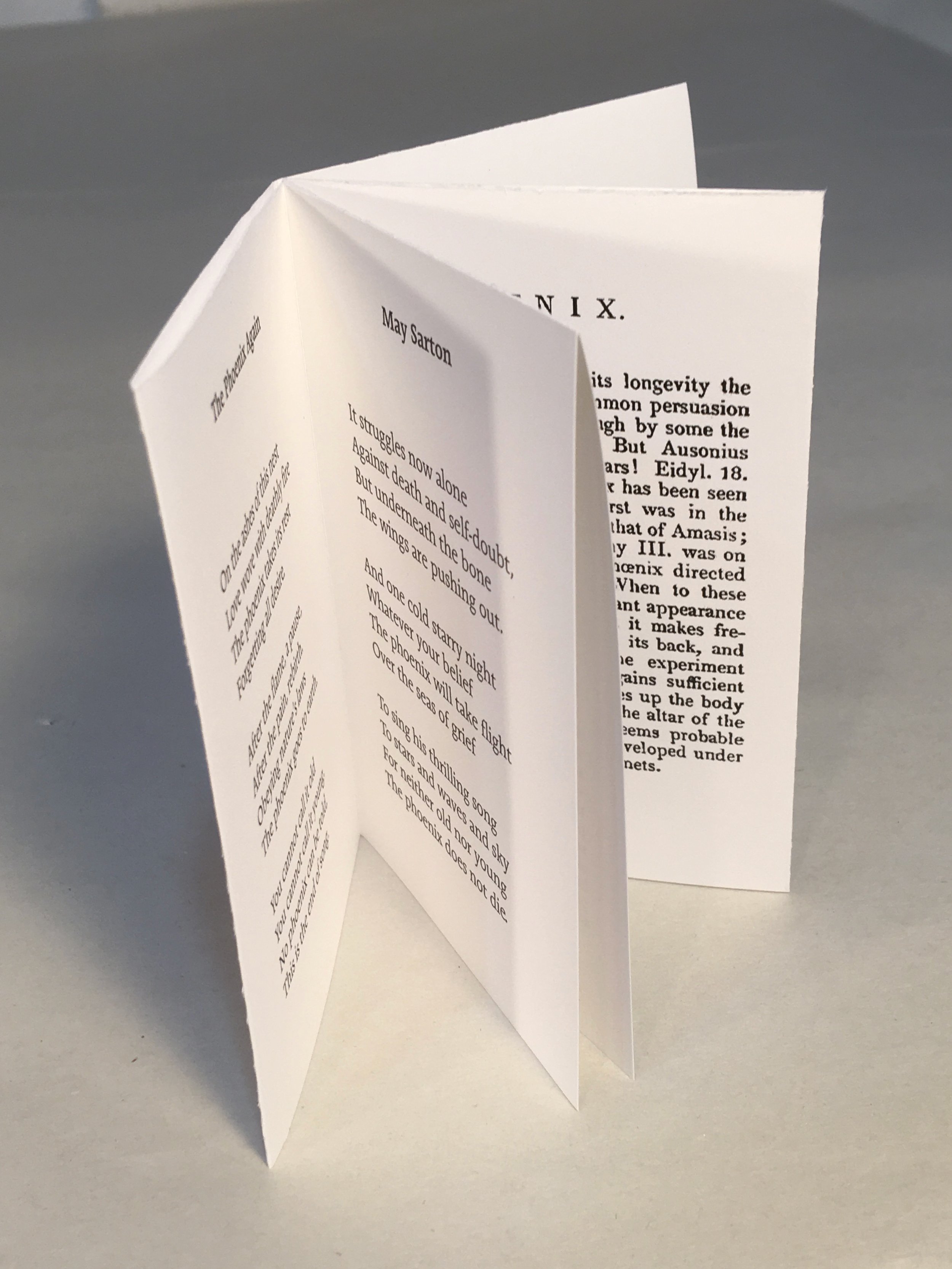

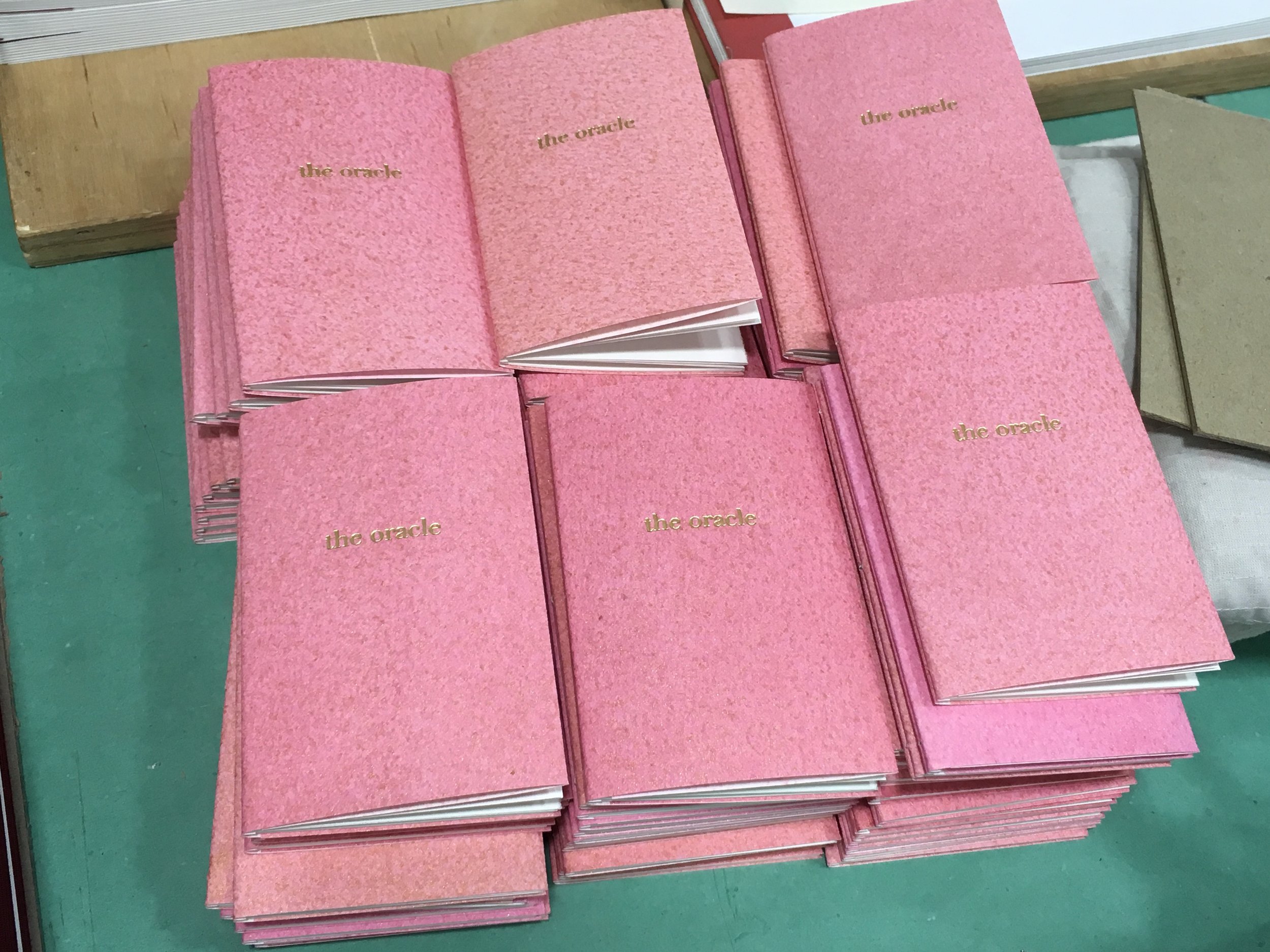

Stephanie Gibbs

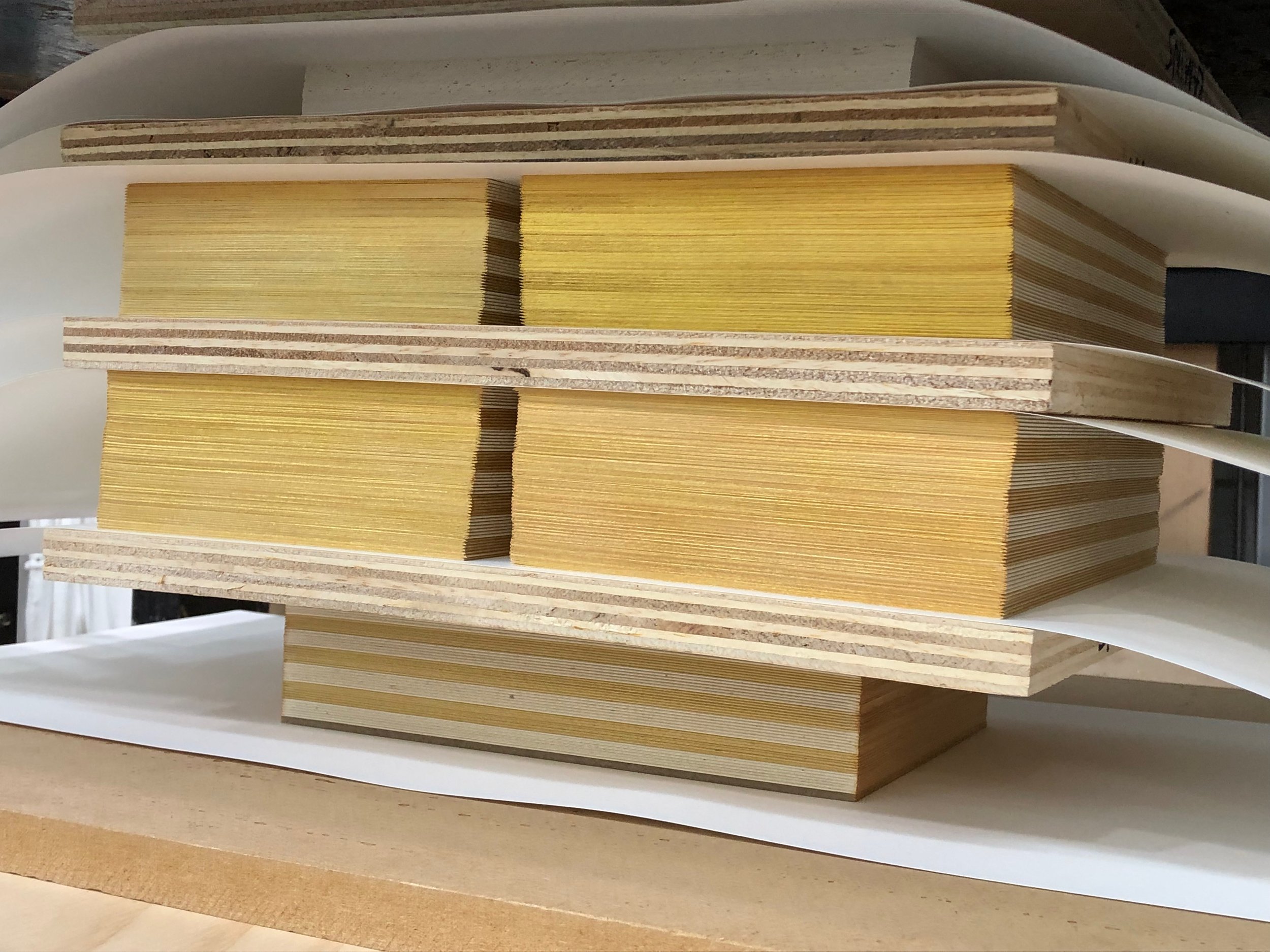

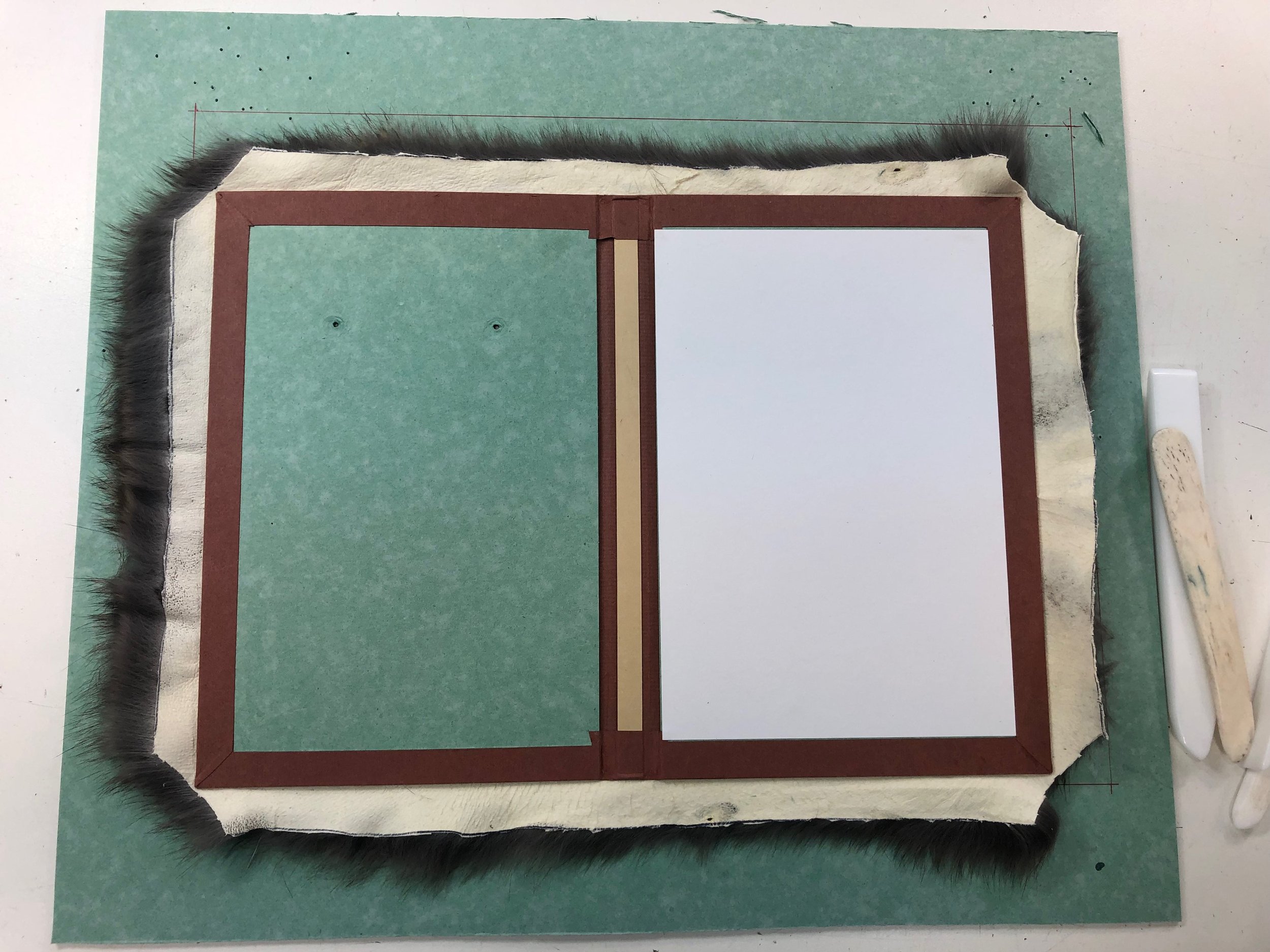

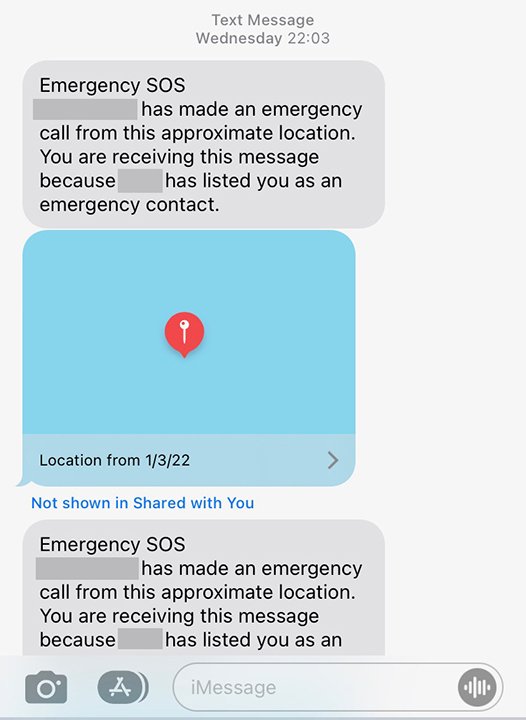

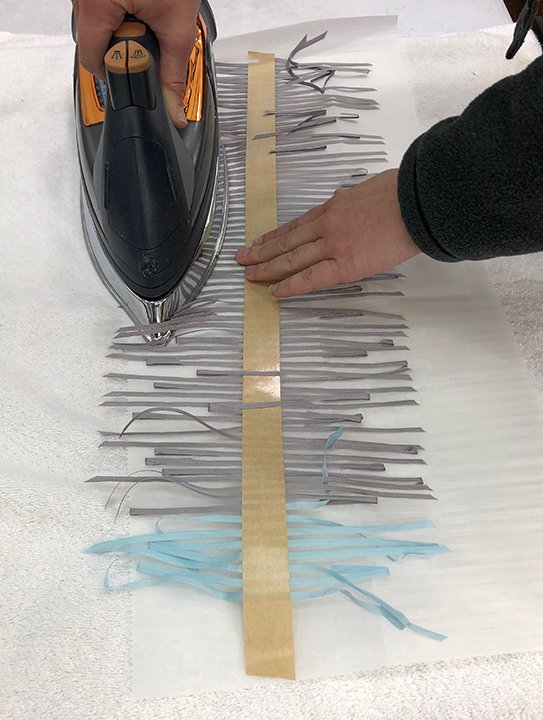

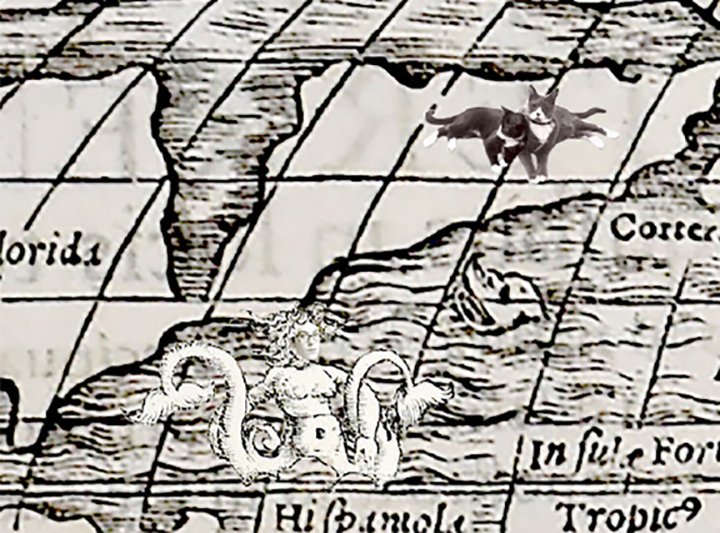

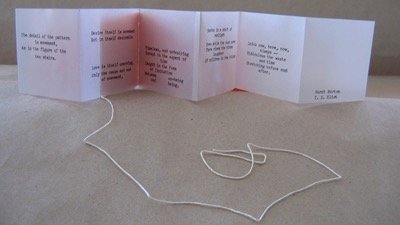

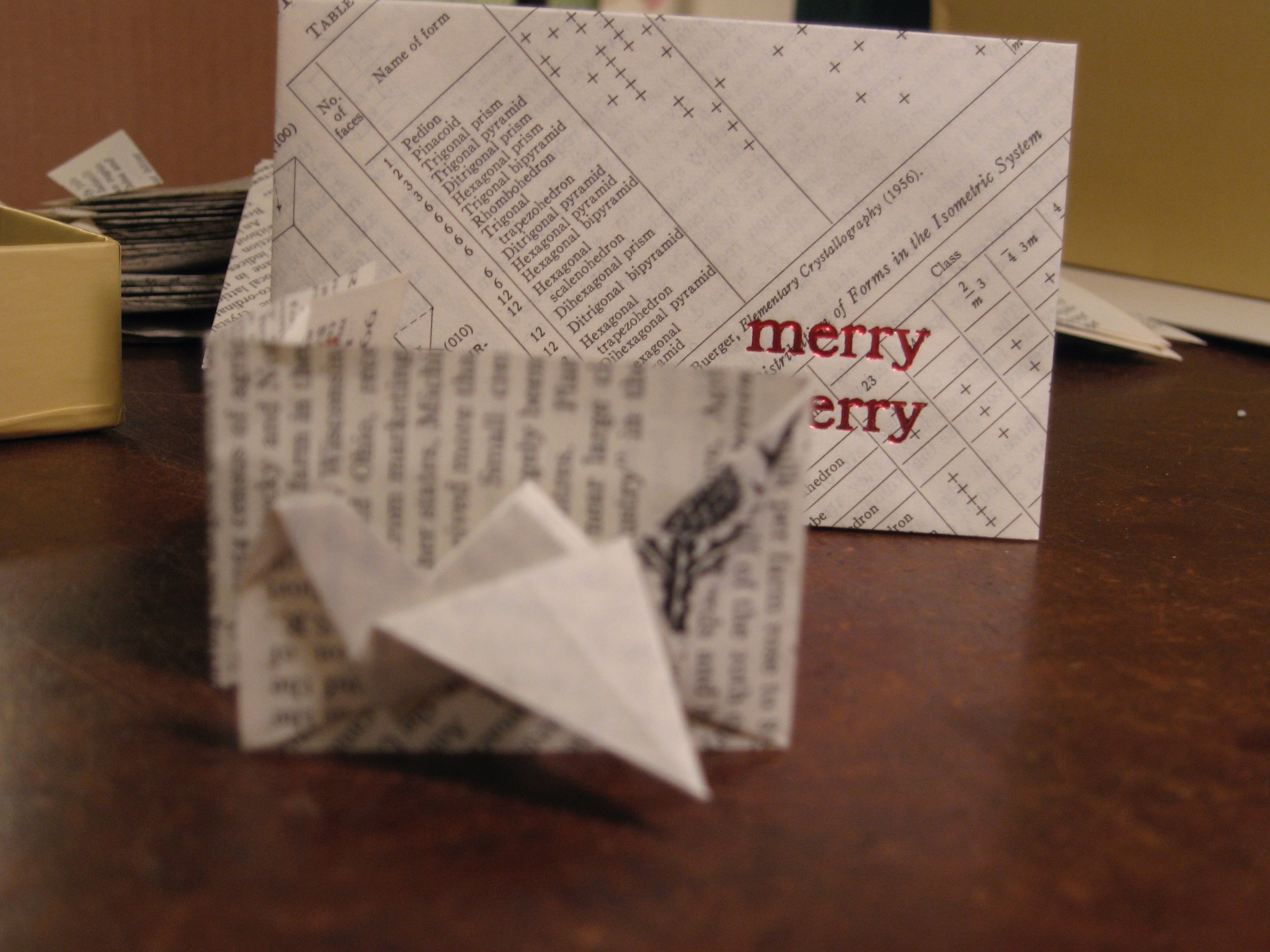

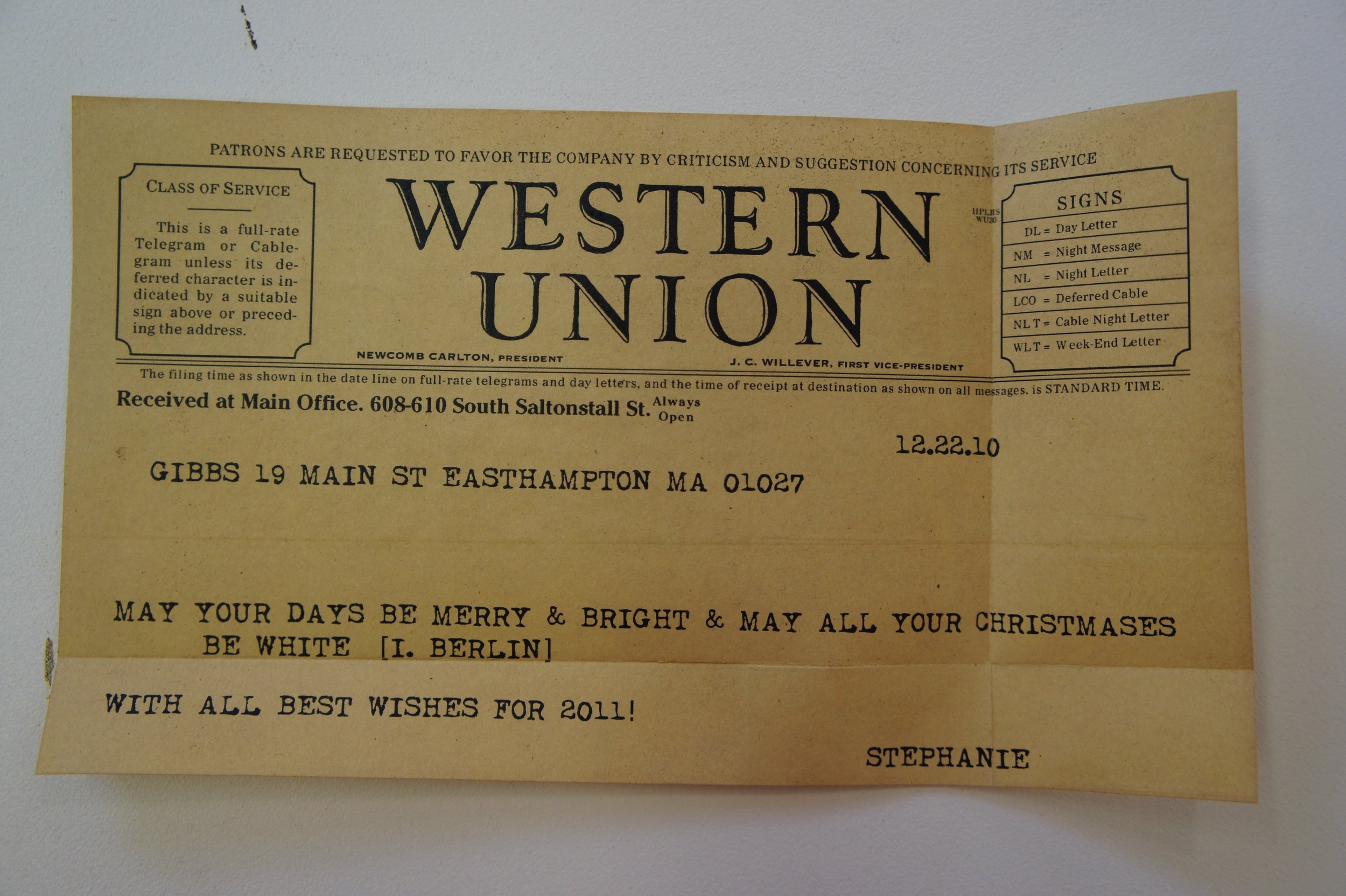

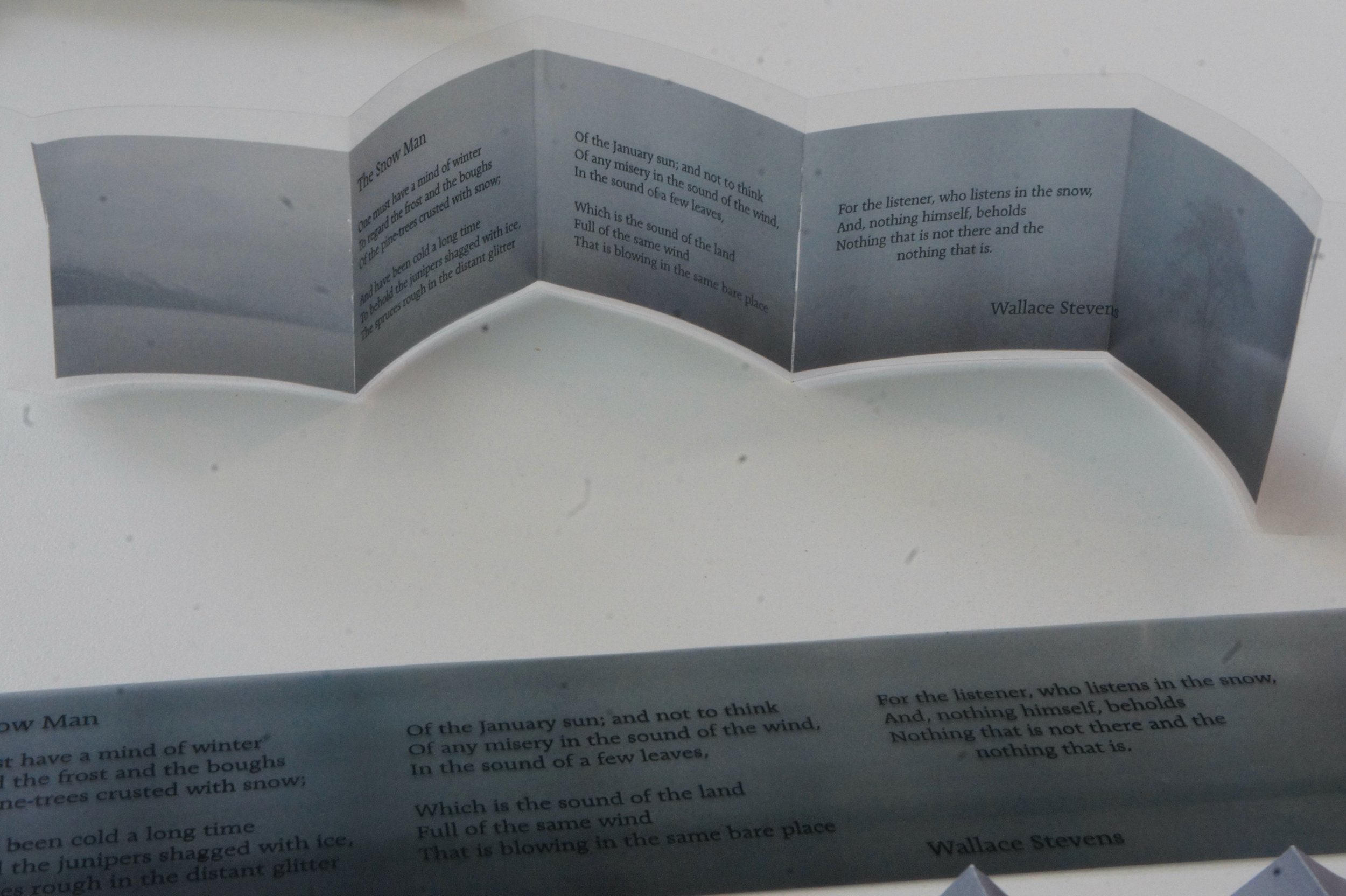

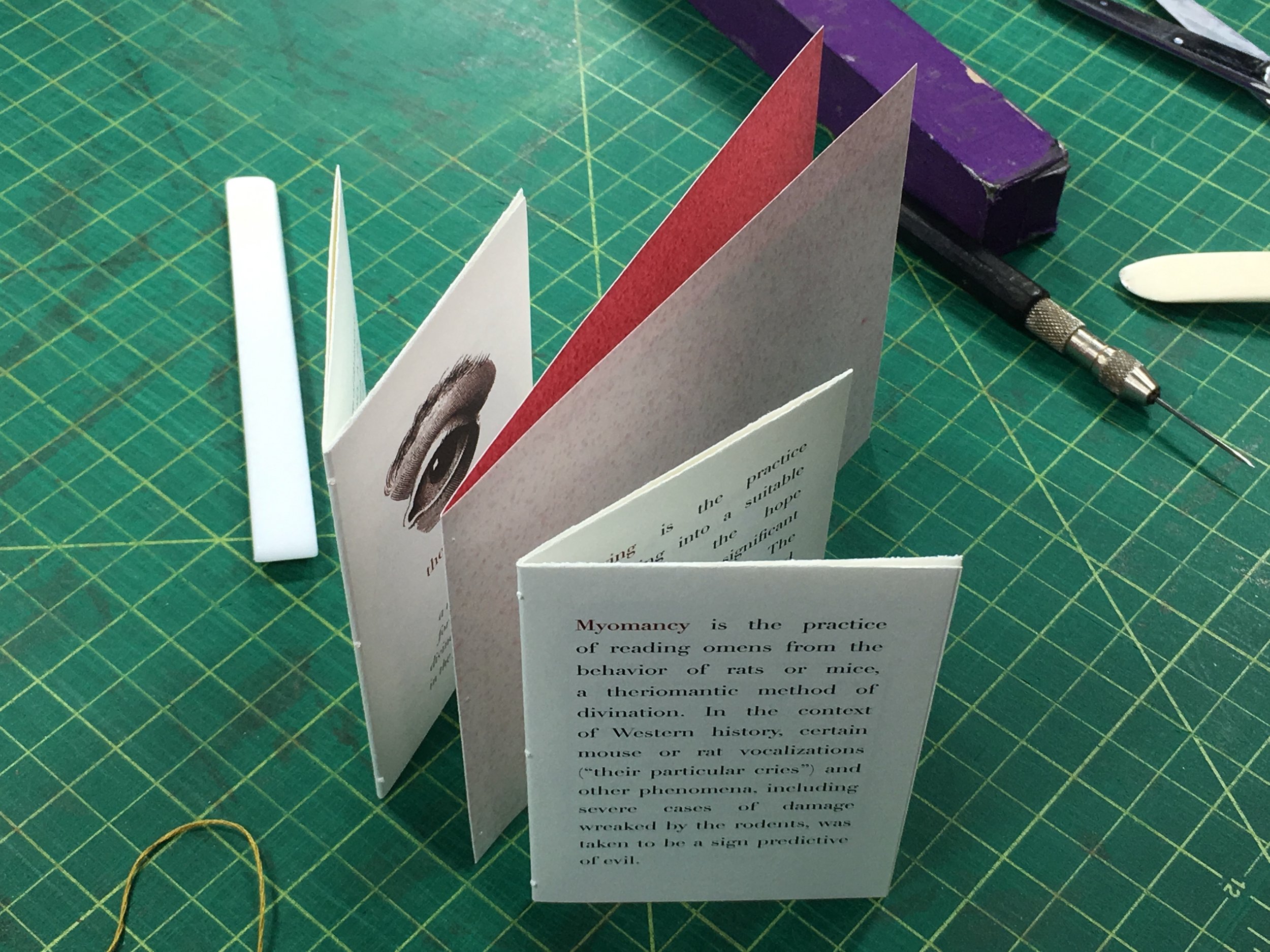

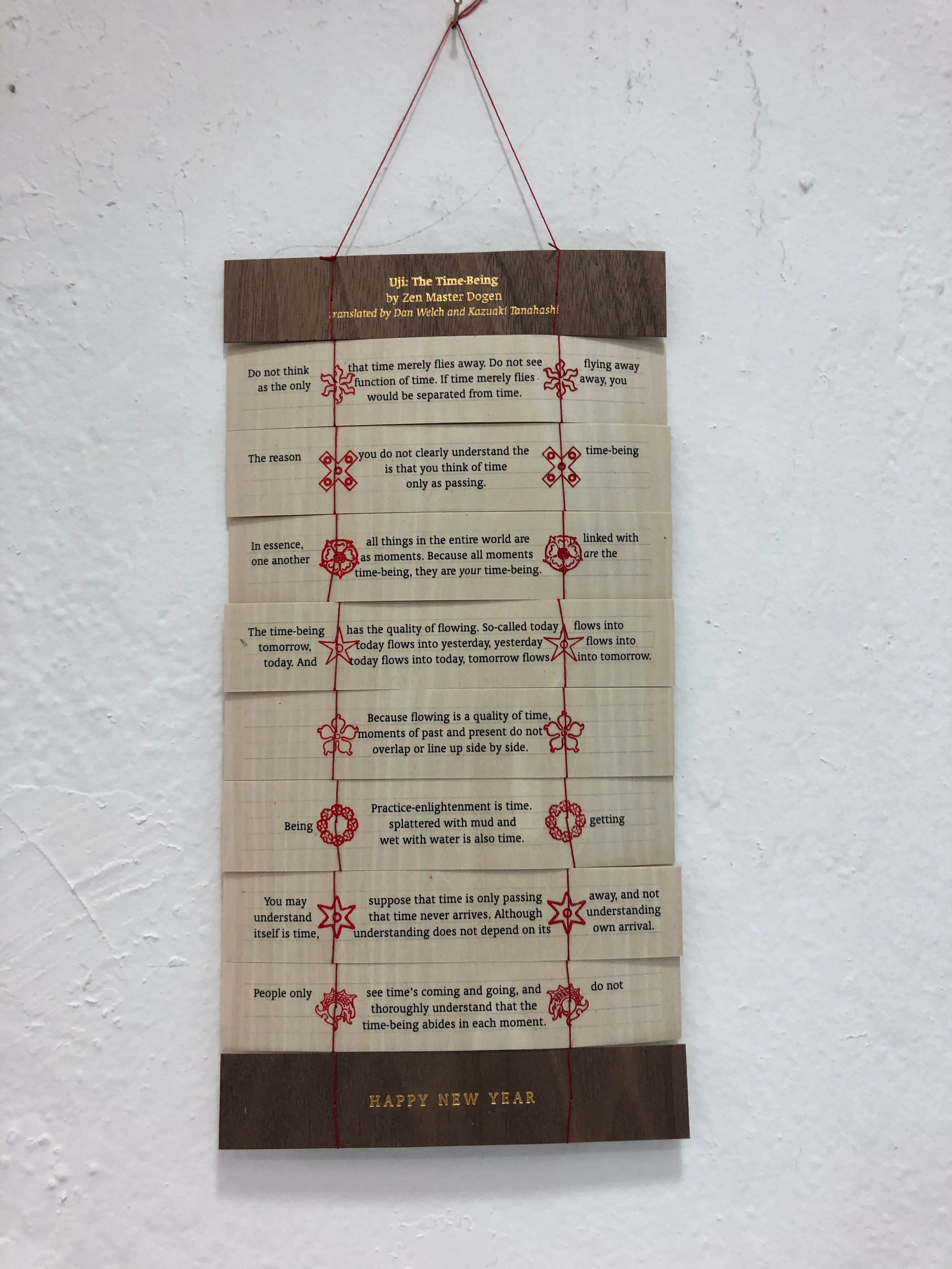

The completion of the 2022 / 2023 holiday edition brings with it a completion of the holiday editions as a project. I started this tradition in my second year of graduate school, with the 2003 / 2004 cards: a project to fill the anxious moments of end of term assessments. During the intervening years, they’ve been a source of joy, an expression of curiosity, a way of trying out new techniques and new materials, and a chance to be frivolous in a way that my normal studio practice didn’t always permit. There have been years when the holiday edition has been the only purely creative project that I’ve undertaken; there have been years when my brain was ricocheting in hundreds of directions and the edition delivered well beyond the “holiday season;” there have been years when I’ve finished the edition and felt a great sense of accomplishment at the outcome.

And now it has been twenty years of holiday editions, and I feel like they have fulfilled their purpose. I have a more dedicated creative process which co-exists with my studio process; the edition itself has grown into a fuller artist-book undertaking than I ever intended for it to. In future years I will probably continue with holiday cards, but with reduced ambition, as my focus turns towards other ways of realizing my projects.